Cancer is a disease of abnormal, unregulated cellular growth that can lead to the formation of solid tumours in bone or soft tissue, or abnormal cells in the bloodstream (haematological cancers like leukaemia). One in two Australians will be diagnosed with a form of cancer before their 85th birthday. Medical treatment for cancer can include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, hormonal therapy and immunotherapy. An increasing number of people live with the side effects of cancer and its treatment for many years. This has shifted how the health community thinks about cancer, and it is now considered a chronic disease.

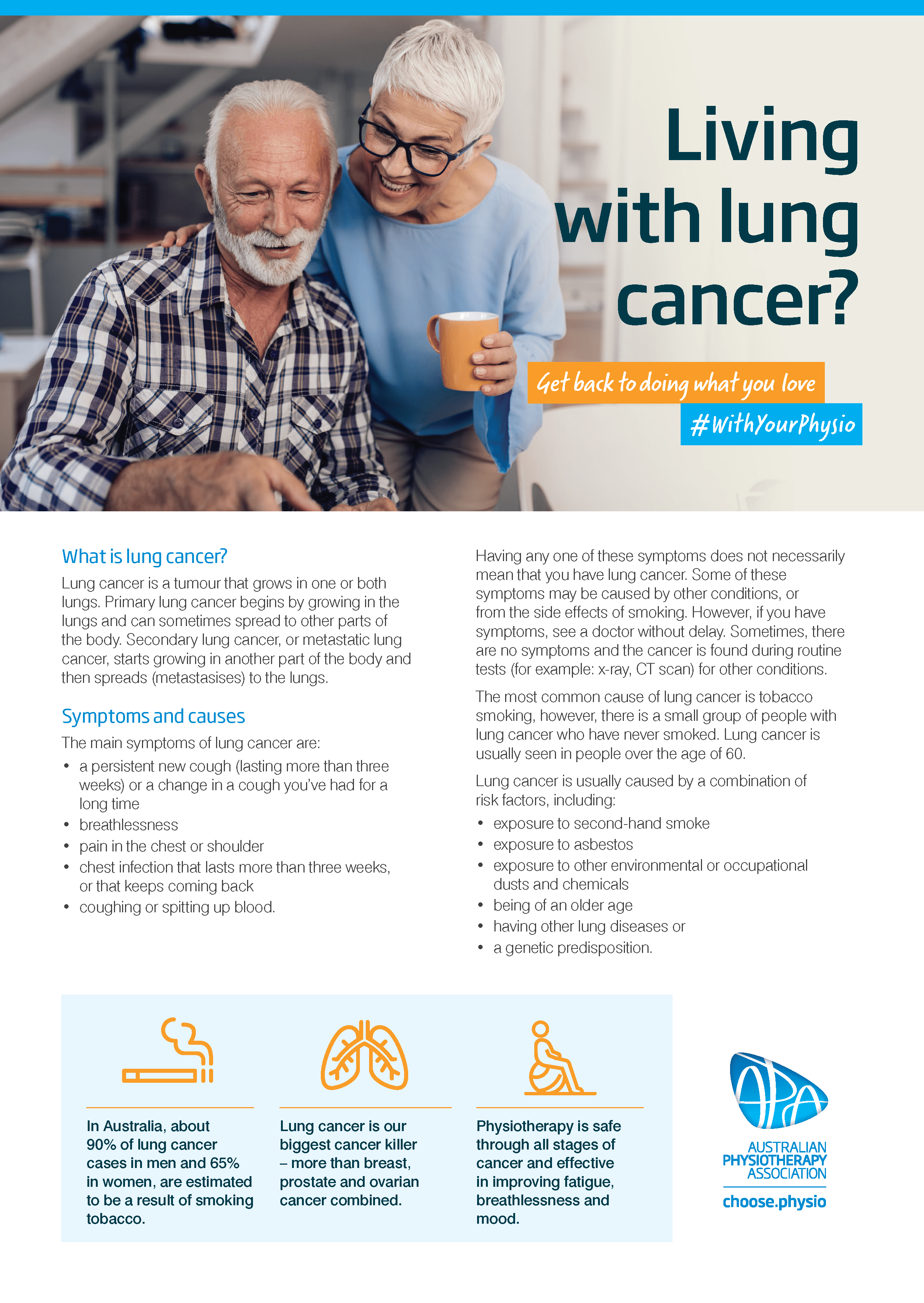

--Spotlight on lung cancer

Lung cancer is a tumour that grows in one or both lungs. Primary lung cancer begins by growing in the lungs and can sometimes spread to other parts of the body. Secondary lung cancer, or metastatic lung cancer, starts growing in another part of the body and then spreads (metastasises) to the lungs.

Click the image to download the factsheet.

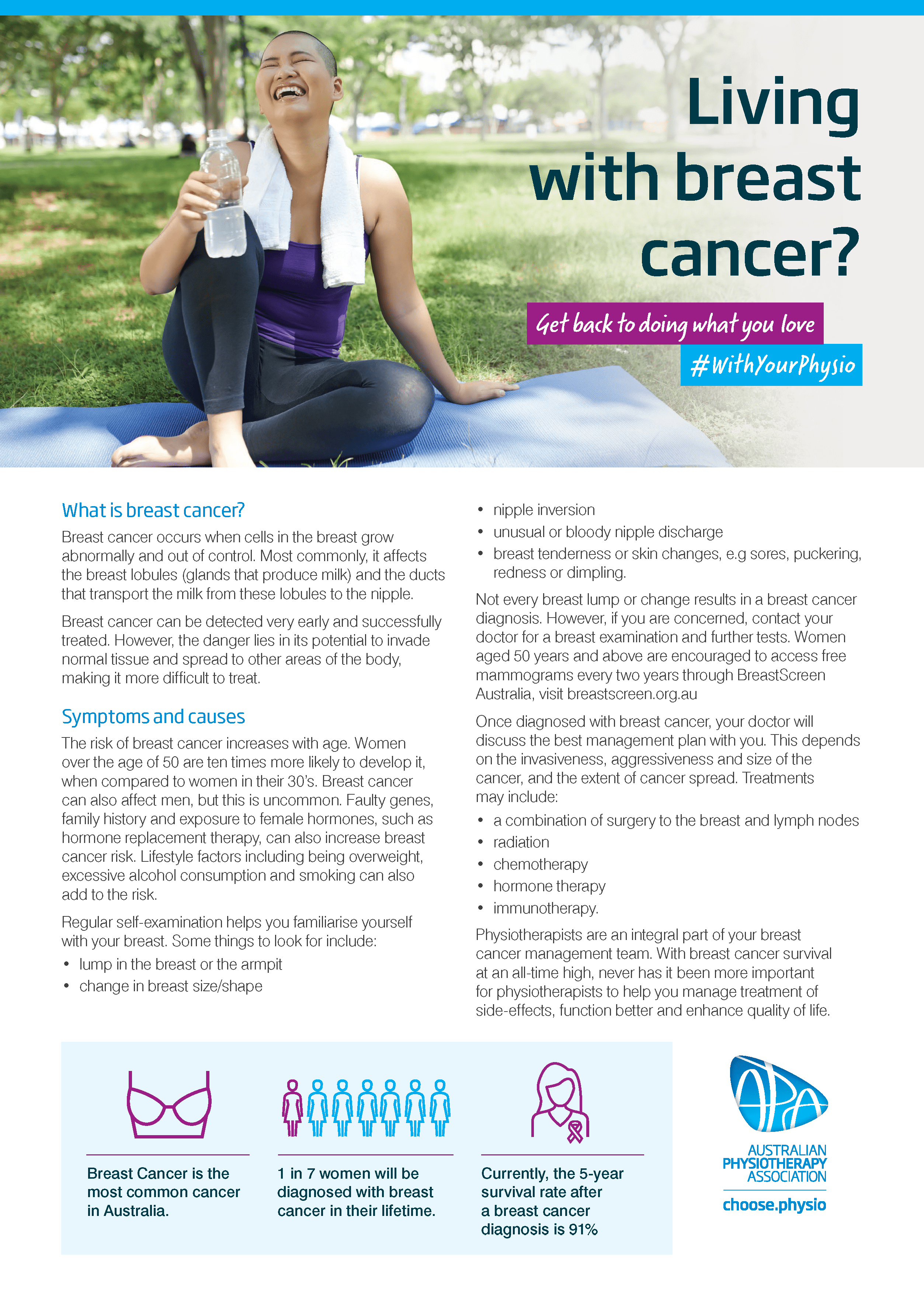

--Spotlight on breast cancer

Breast cancer occurs when cells in the breast grow abnormally and out of control. Most commonly, it affects the breast lobules (glands that produce milk) and the ducts that transport the milk from these lobules to the nipple.

Breast cancer can be detected very early and successfully treated. However, the danger lies in its potential to invade normal tissue and spread to other areas of the body, making it more difficult to treat.

Click the image to download the factsheet.

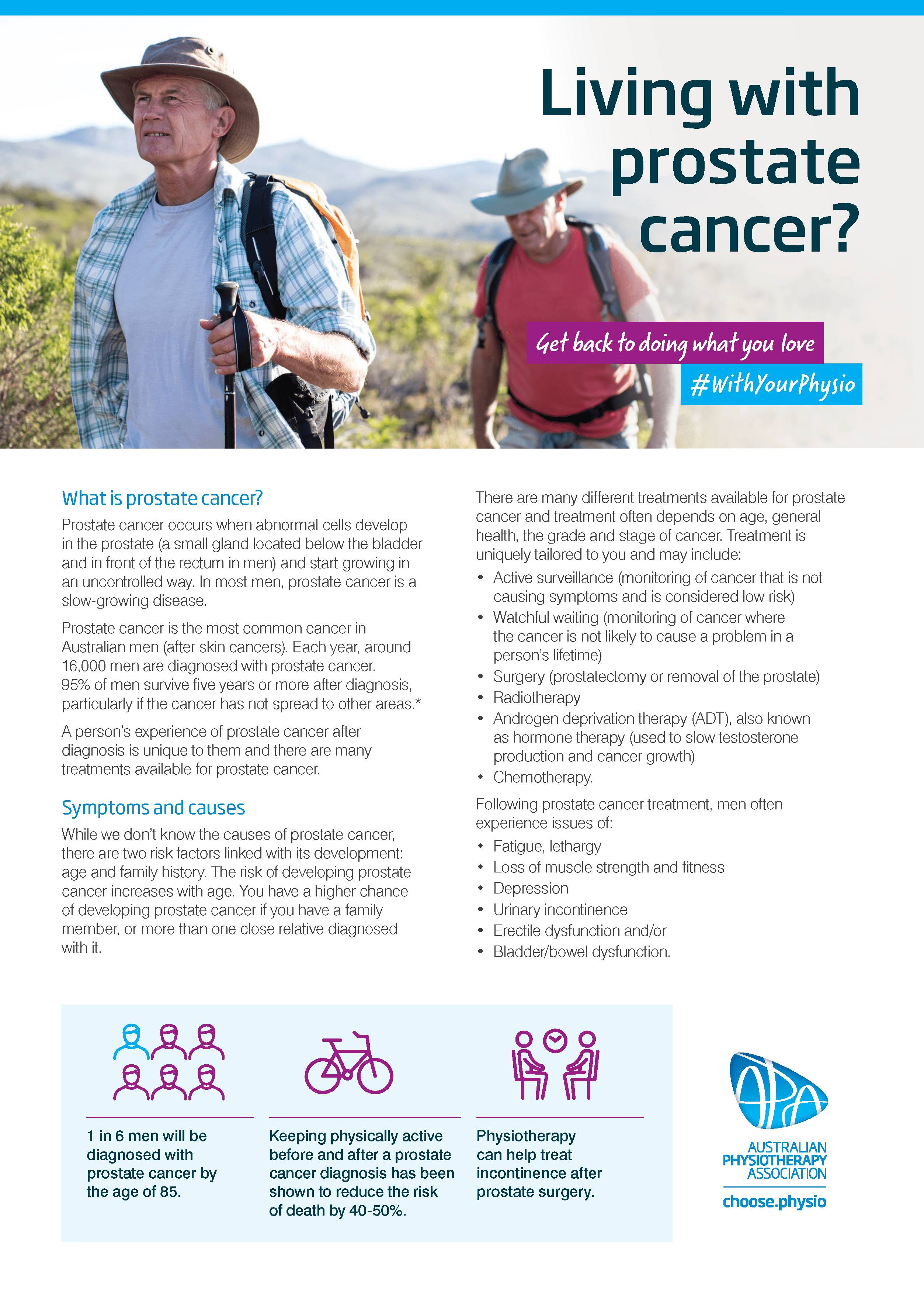

--Spotlight on prostate cancer

Prostate cancer occurs when abnormal cells develop in the prostate (a small gland located below the bladder and in front of the rectum in men) and start growing in an uncontrolled way. In most men, prostate cancer is a slow-growing disease.

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in Australian men (after skin cancers). Each year, around 16,000 men are diagnosed with prostate cancer. 95% of men survive five years or more after diagnosis, particularly if the cancer has not spread to other areas.

Click the image to download the factsheet.

-- What is cancer?

Cancer can occur in any tissue within the body. In Australia, the most common cancer for women is breast cancer, and for men, prostate cancer. Other common forms of cancer are melanoma, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare estimates that on each day in 2019, 396 new cases of cancer will be diagnosed on average, and 136 people will die from cancer on average.

The four most significant risk factors for a variety of cancers are modifiable factors: smoking tobacco, overweight and obesity, poor diet, and physical inactivity. Genetics also play a role in an individual’s risk of developing cancer. Persistent viral infections are now understood to cause cancer, such as the human papillomavirus in cases of cervical cancer.

As a result of screening programs like mammograms and bowel cancer kits, the proportion of Australians being diagnosed with early-stage cancer is increasing. Early-stage cancer responds better to curative treatment, and survival rates do increase with early detection.

--What treatments are available?

The type and size of the cancer will influence the medical treatment recommended, as well as the health and age of the person with cancer.

Surgery can remove solid tumours, as well as other affected tissue such as lymph nodes.

Radiation therapy delivers high energy particles into the body to kill cancer cells. Healthy cells within the field are also affected. The healthy cells do grow back, however this can be the cause of many of the side effects of radiation therapy, such as skin redness.

Chemotherapy is a drug administered via tablet or via a drip to find and kill cancer cells within the body.

Hormonal therapies like Tamoxifen (breast cancer) or androgen deprivation therapy (prostate cancer) suppress either female or male sex hormones, which in turn suppresses the growth of these tumours.

Immunotherapy is an emerging area of cancer treatment that aims to boost a person’s own immune system to attack the cancer cells.

-- What side effects could I experience from these treatments?

The most common side effect across all cancers is cancer-related fatigue. This form of fatigue occurs regardless of recent levels of physical or mental activity. It is persistent and distressing, doesn’t get better with rest, and interferes with everyday life.

Other side effects can include: pain; lymphoedema (swelling); gaining or losing weight; lowered immune function; peripheral neuropathy (tingling and/or weakness in the hands/feet); nausea and vomiting; loss of lean muscle mass; cardiac toxicity (damage to the heart muscle).

Changes to muscle and joint function can occur after surgery, for example shoulder stiffness (breast cancer); neck stiffness (head and neck cancer); pelvic floor muscle weakness (gynaecological and prostate cancers).

-- How can exercise help with these side effects?

Exercise can improve the majority of side effects of cancer treatment:

- Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise improves cancer-related fatigue

- Specific muscle strengthening and flexibility exercises can improve joint and muscle pain

- Being more physically active in general can also improve muscular pain

- Exercise is a routine component of lymphoedema management

- Exercise can be used to control weight gain, and stimulate appetite if weight gain is the aim

- Exercise can stimulate immune function

- Balance retraining improves function in people with peripheral neuropathy

- Resistance training (i.e. lifting weights) stimulates the growth of lean muscle mass

- Aerobic (cardiovascular) exercise improves heart health, and reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease

In addition, exercise improves mood (mental and emotional health), and can provide people with a cancer diagnosis with an important sense of control over an aspect of their treatment.

--What other effects does exercise have?

People who exercise were found to be at reduced risk of developing a secondary cancer when compared to those who did no or little exercise.

As many cancers are associated with modifiable factors such as physical inactivity, becoming more physically active can have flow-on effects to reducing other lifestyle-related diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

There is emerging research that suggests being physically active during chemotherapy treatment helps patients to tolerate the treatment, and therefore receive the full dose of treatment. This in turn means the treatment is more effective at killing the cancer.

-- How do I know it is safe to exercise?

Before providing you with an exercise program, your physiotherapist will conduct a thorough assessment of your general health and physical fitness. They will seek medical clearance from your doctor if they have any concerns about your medical safety to exercise. The exercises prescribed to you are individualised to your specific needs, your current level of physical fitness, your stage of recovery, and your exercise preferences. Most importantly, your exercise program will be in line with your goals and what you want to achieve.

--What kind of exercise might my physiotherapists prescribe?

New guidelines released in 2019 recommend the following prescription to address health-related outcomes due to cancer diagnosis and treatment:

- Moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, 3 times per week, for at least 30 minutes per session

- Resistance (strength) training, of moderate intensity, at least 2 times per week, using at least 2 sets of 8 to 15 repetitions

It is important to know that this is not the starting point – this level of activity should be worked up to and then maintained. Your physiotherapist will assist you in developing a graduated exercise program to work towards these targets at your own pace.

Aerobic exercise (also known as cardiovascular exercise) makes you puff and pant, and gets your heart racing. Some examples of aerobic exercise are: walking, cycling, jogging, swimming, playing tennis, and group exercise classes at the gym.

Resistance training (also known as strength training) involves strengthening major muscle groups against resistance – either your own body weight, resistance bands, free weights, or machine weights.

Use the talk test to figure out what intensity you’re working at:

- If you can sing whilst you are exercising, you’re working at a light intensity

- If you can talk in phrases, but not full sentences, you’re working at a moderate intensity

- If you cannot talk at all, you’re working at a vigorous intensity

Your physiotherapist may also prescribe specific exercises to you to target specific impairments, such as shoulder stiffness, lymphoedema, or poor balance. These exercises are also important, and can be integrated into other forms of activity like those described above.

If you find exercise daunting, remember that doing something is better than nothing, and doing a bit more is better than doing a little bit. Speak to your physiotherapist about finding a program that is right for you.

--I am having difficulty starting to exercise. What should I do?

Your physiotherapist can help you to start small, build success, and set goals. At the very beginning, the aim may be to spend less time sitting. This may look like doing jobs around the house and garden. Your physiotherapist may suggest exercises you can do within your own home, like standing up from a chair, or walking up and down your staircase. Walking is a great aerobic exercise to start with – you can take a friend, go a short way around the block, and use the cool of the early morning or late afternoon if hot weather is an issue.

-- I feel too tired to exercise. What should I do?

Your physiotherapist can help you start with short, simple exercise sessions that you can do during the time of day that you feel the best. Exercise is the most effective treatment for cancer-related fatigue – building up your physical strength will help you cope with the fatigue. Other things to do to maximise your energy levels for exercise: avoid the hottest time of day; wear loose and comfortable clothing; wear a hat if outdoors; listen to upbeat music; have something to eat 2 hours before your session; and drink plenty of water to stay hydrated.

--My cancer can't be cured. Should I be exercising?

Yes – people with advanced cancer still benefit from exercise, and can exercise safely. The focus of exercise for people with advanced cancer is to maintain strength and function so that people and their families can participate in activities that they enjoy, and remain safely at home as long as they want. Your physiotherapist can help you plan exercises around your goals, and help you manage symptoms such as shortness of breath, pain, and swelling.

-- I'm not keen on going to the gym. Is there anything else I can do?

Yes! Exercise doesn’t always have to take place in a gym. Your physiotherapist can prescribe a program for you that you can perform within your own home, with equipment you will have available – chairs, floor space, and everyday items around the home. There are other spaces within the community that make great places to go for a walk – shopping centres, art galleries, and local parks. Think about what environments you enjoy being in, and discuss with your physiotherapist about how you can be physically active in these spaces.

--Factsheets

Get back to doing things you love, with your physio.

Download the factsheets about prostate, breast or lung cancer to see how physiotherapy can help you.

--What next?

GO TO

choose.physio/find-a-physio To find your nearest Cancer, Palliative Care and Lymphoedema physiotherapist.

CHOOSE

‘Cancer, Palliative Care and Lymphoedema’ option under special interest area in the ‘refine your search’ drop-down box.

--Are you an APA member?

Access your exclusive member-only campaign toolkit.